When we talk about optionality in software, we're talking about trade-off spaces. An app that could generate you a dollar today, or one that could generate you 10 dollars tomorrow? Neither is 'right' or 'wrong'; they are simply the different outcomes we can optimise for. The clearer we understand this space and the fact we're always going to make compromises in some way, the more constructive thinking and discussions we can have around these decisions.

This is the fundamental purpose of this series. For much of my career, I have witnessed (and played an active role in) this trade-off space being ‘fought’ between opposing forces. On the one side, we typically see software engineers, and on the other stakeholders in the business (founders, executives, product managers, etc.) It's often an unproductive and unnecessarily divisive conversation because each side tends to fail to appreciate the motivations driving the other party.

Commonly, business interests see engineers ‘wasting time’ on practices like writing documentation, adding tests, and cleaning up tech debt, that deliver no new features or functionality and thus seem to have no business impact. Meanwhile, engineers can often be divorced, sometimes willingly so, from business realities. They get frustrated that they can't get on and build things in peace without distractions, unclear requirements, and changing priorities. The two sides struggle to appreciate that they're both bringing the vital perspectives necessary to find the correct trade-off in a given situation.

Only engineers will have the technical ability, and proximity to the codebase, to understand what the optionality of the software is. No one else will be banging on their door asking them to restructure some code to make it more extensible. But software with greater optionality is more valuable, and thus engineers are the cultivators and guardians of the company's software value.

Similarly, engineers very rarely have the most business context within an organisation - whether that be talking to customers, deeply understanding the market and competitors, or envisioning the future direction of the company. It's not that engineers can't (indeed there is a lot of value in engineers embracing more of this thinking) but there is ultimately a limit of how much they can do this without impacting their ability to build things.1

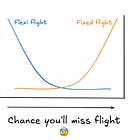

When the business needs value delivered today, investing in increasing the optionality of software is a poor choice; one that engineers are unfortunately liable to make in a vacuum.

Thus we need both perspectives to arrive at the solution. The pressure of delivering something today needs the counterbalance of creating and preserving value tomorrow. If both sides can listen to and acknowledge the other without it being a wastefully combative exercise, the quicker, easier, and more elegantly we can arrive at the right trade-off decision.

Optionality is the lingua franca that can bridge the gap that so often exists between those building software and those who need the software built. Making optionality the conscious driver of our decision-making across every fractal level of our business, from code changes to team meetings to boardroom decisions, ensures the greatest value for our users and ourselves.

Paul Graham’s ‘Maker's Schedule, Manager's Schedule’ covers this succinctly